Reflections on constitutional reform

At any given time in Jamaica, there will be a range of items on the agenda of constitutional reform. In the late 1970s, Michael Manley’s Administration raised a variety of issues, and sought to give structure to aspects of the debate. Subsequently, the Constitutional Commission was party to deliberations and recommendations relating to changing structural features of the Constitution. Similarly, in 2011, the Jamaica Labour Party (JLP)Government brought into law the Charter of Rights and Freedoms, which revised Chapter III of the Constitution in various ways.

And there have been other steps along this political road. Recall, for instance, that the primary objective of the National Democratic Movement in the 1990s was constitutional reform, with the party unsuccessfully willing the country to depart from the Westminster system of governance.

In some instances, the effort at constitutional reform is taken as a substantial, root and branch effort, presumably to lead to fundamental reform. In others, though, there are more modest goals, with particular changes contemplated to address a given set of issues. In the latter category, one would perhaps need to place the People’s National Party’s (PNP)attempts to establish appeals to the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) in lieu of our current appeals to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council.

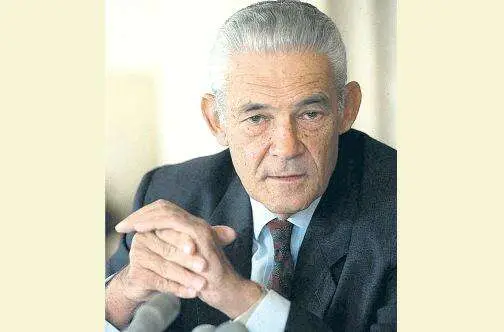

As the Andrew Holness Administration takes up the mantle of authority in Jamaica, it will, of course, be concerned with questions of immediacy, including issues with significant fiscal implications, and issues of relating to governmental appointments. Presumably, at some stage, the administration will also need to consider certain issues of constitutional importance. What are some of these issues, and how should they be tackled?

THE CCJ QUESTION

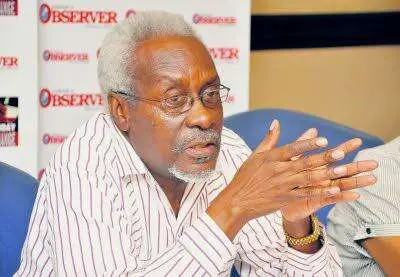

Naturally, the question of the Caribbean Court of Justice will remain on the agenda. It is possible to identify at least three strands of opinion within the JLP on this issue. First, there are those who support retention of the status quo. In this category, the very influential former Prime Minister Edward Seaga has placed himself, but he is certainly not alone. Mr Seaga’s perspective has long been based on the view that the Privy Council, by virtue of its independence and distance from the Jamaican polity, is a source of “pure justice” for Jamaica.

Secondly, there are persons within the JLP hierarchy who place emphasis on procedure, without firmly taking a stand on whether the Privy Council should go. They argue that the people of Jamaica should be given an opportunity to decide on Jamaica’s final court, and that opportunity should be made available in the form of a referendum. The referendum school within the JLP is led by Prime Minister Holness. It is built on the idea that the people of Jamaica now have a right of appeal to the Privy Council, and that if this right is to be taken away, the people should be consulted.

The third, discernible strand of opinion within the JLP on this issue supports abolition of appeals to the Privy Council, but would put in its place not the Caribbean Court of Justice, but rather a Jamaican final court of appeal. This position, which has been advocated by Minister of Justice Delroy Chuck for many years, is built on the premise that a Jamaican final court would have all the virtues of the Caribbean Court of Justice, and none of its disadvantages. So it is noted, for instance, that the CCJ, like the Privy Council, is not a court emanating from the sovereign State of Jamaica. It is a court which combines the needs and interests of several sovereign entities. Chuck and Co may thus be heard to argue: Why does Jamaica need to enter into a court with mixed sovereignties that may include nationals of countries that do not even like us?

REFERENDUM?

One way for the JLP to reconcile its internal differences on this matter would be for the Government to call a referendum, and to put forward a united position on its side. The PNP will presumably be united in favour of the Caribbean Court of Justice. If the JLP also comes down in favour of the Caribbean Court, then there is every likelihood that this court will be established. On the other hand, if the JLP is united in favour of the Jamaican final court, or, in favour of retaining the Privy Council, the situation will probably be a close call.

In any case, this matter seems to require resolution within the lifetime of the Holness Administration. The debate has been proceeding in earnest since at least 1990; the matter has been addressed by the Privy Council, it has been addressed in various party manifestos; the PJ Patterson Administration and others since then have diligently paid Jamaica’s dues for the Caribbean Court of Justice, and the Court has patiently awaited Jamaica’s arrival to the appellate jurisdiction — for more than a decade.

FIXED ELECTION DATE

A second constitutional issue that may require attention during the life of the current administration concerns the fixing of a date for the General Election. The JLP has placed itself on record in support of the fixed date for general elections in the country, and they appear to have garnered some support for this approach. The Electoral Office of Jamaica has come out in favour of a fixed date, on the basis of administrative convenience, and the suggestion coming from Senate President Tom Tavares-Finson, has been that uncertainty relating to the election date has prompted significant costs to the country.

Those who support the fixed date election may also build their argument on the basis of fairness. The point is that when the election date is subject to the decision of the incumbent prime minister, then the governing party has an inbuilt advantage in any upcoming election. The governing party will know how to allocate its expenditure most efficiently, and, at least in theory, may leave the opposition party in the dust by calling a ‘snap’ election.

But the fixed date approach also has its detractors. For example, former Prime Minister Seaga opposes it largely, it seems, on the basis of its inflexibility. If the date for a general election is fixed, then the prime minister will have very limited ability to control wayward or lazy parliamentarians, especially in the context of a tight division of seats between the two parties in parliament. When the date is not fixed, the prime minister may use the threat of a snap election to bring such parliamentarians into line.

FLEXIBILITY AND WESTMINSTER

Moreover, as Mr Seaga also argues, the fixed election would remove power implicitly held by the Jamaican electorate. In the current arrangements, if a government is underperforming, or to be more precise, if the people want to change a government, they may bring pressure on the prime minister to call elections early. This pressure, whether it is through the device of a no-confidence vote in parliament, or through street protests and so forth, may bring about a change in government, or at least force a government to change its ways. If, however, the election date is fixed, there is no significant way of booting an incompetent administration from power before its due date.

It should also be noted that some members of the PNP have traditionally supported the current, flexible date system, largely by reference to the view that the fixed date approach is not compatible with the Westminster System. That line of argument has lost some of its force, for, following the Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011, the British Parliament and British Governments are now placed on a fixed, five-year schedule. The British approach allows for two exceptions to the five-year rule, namely, when there is a successful no-confidence motion in the House of Commons, or when two-thirds of the members of the House vote for an early election. So, it seems that the British have found a way to address the ‘no confidence’ aspect of Mr Seaga’s opposition to the fixed date approach.

SCARCE BENEFITS

One final aspect of the fixed term debate may need further ventilation. It is sometimes argued that the uncertainty in the current system promotes unrest and political tribalism. I am not sure that this is correct. True, if the prime minister may time the distribution of scarce benefits and spoils to coincide with undeclared election plans, this will prompt resentment among those excluded from the largesse. But it is not the uncertainty about the election date that prompts the resentment; rather, it is the unfair allocation of the resources.

To take the point further: assume that everyone knows that the election date is June X, 20YY. Nothing in this fact would prevent the incumbent government from allocating resources unfairly all the way up to June X, 20XX. It is not the date that prompts the misallocation of the resources — that may well continue, regardless of the date. Mechanisms must be put in place to address such misallocation.

In light of the foregoing, the debate on the promised introduction of a fixed date electoral system will be watched with great interest by Jamaicans. In this debate, a thinking member of the House or Senate may well ask whether this is the type of decision that needs to be decided by a referendum. Using the CCJ argument, it could be said that the people now have the right to throw out their government early: if this right is now to be taken away, should not the electorate be consulted? In other words, there is an analogy between the fixed-term election and the CCJ issue which may need to be explored.

THE JAMAICAN SENATE

Another item which Prime Minister Holness may wish to reflect upon concerns the formulation of rules relating to membership of the Jamaican Senate. On this point, the question is whether the Constitution should be amended expressly to ensure that the prime minister and the leader of the Opposition have the power to dismiss members of the Senate whom they have appointed. The question arises because Section 35 of the Constitution, which deals with the appointment of Senators, is silent as to who may dismiss them. This matter came up, in one form, in the noted litigation between Andrew Holness and Arthur Williams, and so, it has been addressed by the High Court and the Court of Appeal.

The question for me is whether, as a matter of policy, it is good that a senator, once appointed, may opt to disregard the political will of the appointing power. Those who believe that the senator should be free from the risk of dismissal for disregarding the appointing power base their viewpoint on the concept of the independence of the Senate or the senators. But, if independence is meant to be central to the work of the Senate, why did the framers of the constitution opt to place appointment power in the hands of the prime minister and the leader of the opposition?

Notice, too, that contrary to the approach taken for instance in Trinidad and Tobago, the Jamaican Constitution makes no provision for the appointment of senators by politically independent entities such as the Church. At its origin, therefore, the general scheme for Jamaica does not seem to have contemplated the type of independence from political direction that some persons now regard as desirable.

The matter requires further deliberation. When Norman Manley, Edward Seaga, David Coore, and others took part in our pre-Independence deliberations, it is doubtful that they envisaged a situation in which one or two senators could wilfully oppose government policy on crucial issues — and do so without the risk of being dismissed. It is at least arguable that if we want this situation to prevail, the Constitution, reflecting the will of the people, should expressly say so.

DUAL NATIONALITY

The Holness Administration may also wish to put the question of dual nationality of parliamentarians back on the agenda. Seven or eight years ago, the Jamaican courts, under the steady guidance of Chief Justice Zaila McCalla, and the then Court of Appeal President Seymour Panton, averted serious constitutional difficulties by their careful, judicious reading of the law. Today, the question of dual nationality is not a hot item; but, for that very reason, now may be the time to clarify matters of uncertainty in this area.

For one thing, the Constitution could be amended to state clearly the circumstances in which a dual citizen may be allowed to remain in parliament. The current constitutional language bars from membership in parliament a person who “by virtue of his own act, under any acknowledgement of allegiance, obedience or adherence to a foreign power or State” (Section 40(2)(a). Would it not be more readily understandable expressly to bar foreign nationals who have not become naturalised citizens of Jamaica?

Significantly, too, the Constitution does not clearly state what is to happen if an unqualified candidate has won in an election. Two clear possibilities arise: (a) the winning candidate should be disqualified and then there should be a by-election; or (b) the qualified candidate who took second place in the election should automatically become the parliamentarian.

The Jamaican courts have decided, in Dabdoub v Vaz that option (a) is the correct approach. And this may well be so; but that decision would be on firmer ground if it were to receive constitutional support. The Jamaican Constitution could spell out what should happen if an elected parliamentarian is found to be ineligible.

DIASPORA AND DUALITY

In any deliberations concerning dual nationality, two additional points should be addressed. One concerns the diaspora. The Minister of Foreign Affairs Kamina Johnson Smith, has indicated that efforts may soon be underway to give the vote to members of the diaspora. This may be popular, but it will be subject to practical difficulties. Nevertheless, if it is to be done, we may well need to change the dual nationality role for parliamentarians. There would, I think, be an implicit inconsistency in saying that Jamaicans living overseas can vote for parliamentarians, but that Jamaicans of dual nationality, even if living in Jamaica, cannot be Members of Parliament.

The other relates to the exception concerning “Commonwealth citizens”. The Constitution intends to treat Commonwealth citizens in the same manner as Jamaicans, but there appears to be a drafting error. Specifically, Section 39 of the Constitution evinces the intention that Commonwealth citizens are eligible to become members of parliament, but this rule is expressly made “subject to the provisions of Section 40”. And then, Section 40 prohibits persons who are foreign nationals by their own act from membership of parliament. Given that the rule allowing Commonwealth parliamentarians is “subject to” the rule barring foreign nationals, then the situation is not at all clear. My guess is that the framers of the Constitution intended to make Section 40, subject to Section 39, and not the other way around. So, this could be corrected.

INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL COURT

Finally, at the constitutional level, there is the question of Jamaica’s participation in the International Criminal Court. There was a time when American opposition to the International Criminal Court may have counselled caution on our part — arguably. But now the United States is no longer seriously opposed to the International Criminal Court, so that reason for reticence on our part has been removed.

Furthermore, Jamaica had once argued that there is a significant constitutional barrier to our participation in the Court — a barrier based on the working of our rule against double jeopardy. But, lo and behold, all Caricom countries save for Jamaica and The Bahamas are now full parties to the International Criminal Court, and many of them have double jeopardy provisions similar to our own. In the circumstances, we could be accused of opposing the court for unstated reasons.

Now, 124 states are party to the Rome Statute. If we need to adjust our constitution in order to join the regime, then the Holness Administration should lead the way. If no constitutional amendment is needed, then that is all the more reason for Jamaica to become party to a court system expressly intended to prevent impunity from specified forms of criminal behaviour.

Stephen Vasciannie, a former Jamaican ambassador to the USA and the OAS, is the professor of International Law at UWI, Mona.