Political awakening (Part 5, final instalment )

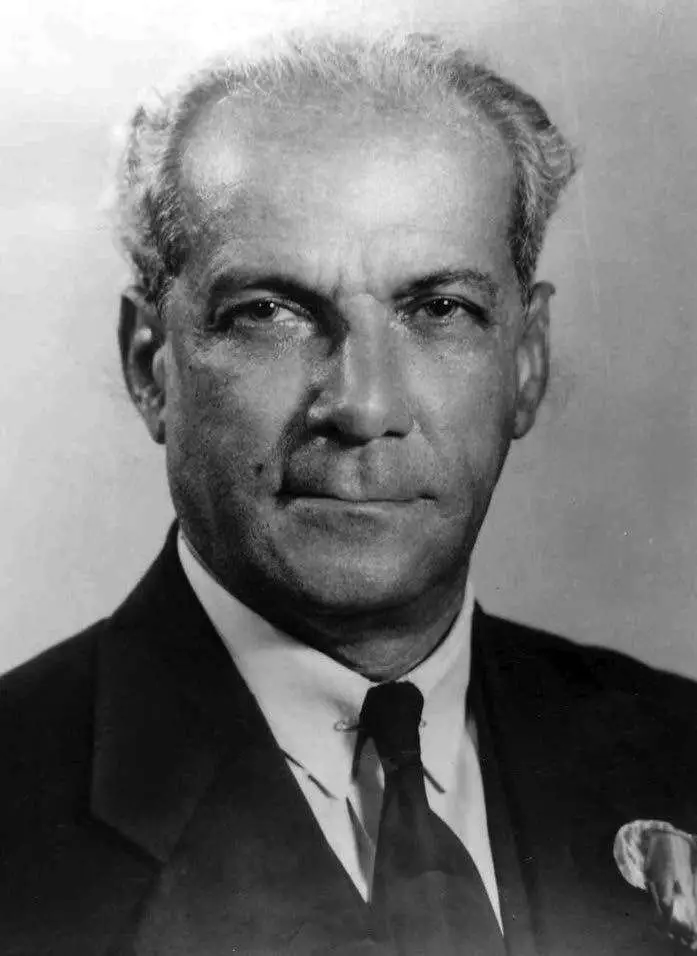

After connecting with the masses, the Jamaica Progressive League went even further in attempting to direct the changes that were to bring about constitutional change in Jamaica by aligning themselves to the first most viable political party, the People’s National Party (PNP), which was founded in 1938. The founders, according to O T Fairclough, were himself, Noel Nethersole, HP Jacobs and renowned barrister Norman Manley who joined after several requests.

The establishment of the party resulted from a conference held in Kingston on August 28, 1938 where there were 50 invited delegates from all over the country. A political party that shared the same objective of the league was considered instrumental in the reshaping of the political agenda and so the league maintained a close association with the party. The PNP was even named by the New York League, according to Federal Bureau of Investigations records, as its foreign principal and the league were instrumental in raising money for the party in its formative years.

The association with the party scored a decisive victory for the Jamaica Progressive League when universal adult suffrage was granted in 1944. The league had long identified this as one of the hurdles to overcome in the movement towards self-government.

Earlier political parties, such as Garvey’s People’s Progressive Party, had failed despite the fact that the base of his support came from the disenfranchised masses, making him popular. With a foothold in the political system, the task of bringing about change was a step closer. Thus, Reverend Ethelred Brown marked it as an accomplishment, stating:

‘In spite of the fly in the ointment, namely increased veto power to the government, the granting of universal suffrage is a victory for your league.’

In Jamaica, meetings of the league and PNP were attended by representatives of both groups. Members of the league, such as WG McFarlane and Walter A Domingo also became members of the party. Domingo was especially integral to the party in its formative years as he was constantly called upon by the party to provide guidance.

The continued association with the party was to ensure that the principal mandate of the league was carried out, especially considering that Manley, the president of the PNP, and a small group of his supporters, wavered on the issue of self-government. Manley’s indecisiveness about the issue of self-government manifested itself from as early as the conference on August 28, 1938 at the Silver Slipper Club in Cross Roads. Here, he noted, “I do not say that I think Jamaica is today ripe for self-government, but I claim that we must start a movement working which will help us to become ripe for it. And the more discipline, the more honesty we can show, the quicker we will reach that stage.”

The situation did not change much in subsequent years. Manley continuously deviated from the path that the Jamaica Progressive League tried to steer him towards. His ambivalence about self-government might have been grounded in the same fears that Hugh Buchanan had expressed in his letter to Public Opinion. The party under Manley’s leadership, however, showed signs of falling back in line in the early 1940s when the relationship with the colonial government broke down as a result of the arrest of Domingo. But no sooner than things calmed down, he was settled in his old uncertainties.

He was instead fixated upon federation, which he viewed as a more viable option. This, of course, was more in line with the policy of the imperial power as they strove to create a ‘partnership’ through the introduction of the Colonial Development and Welfare Act (1940) which, as Trevor Munroe noted, meant “in economic terms, the provision of material assistance in the ostensible interest of modifying the colonial economy and improving colonial social welfare”.

Alexander Bustamante also withdrew his support for self-government, claiming that “the time has come for a broader constitution where the Government should not have a majority in Executive Council … but if we got complete self-government here now, there would be bloodshed night and day”.

Given that these two leaders were not enrolled in the vision of the Jamaica Progressive League, it is interesting that the league never seriously attempted to establish themselves as a political party even though they declared this much when the relationship between the two groups deteriorated to such an extent that there was a separation in the late 1940s. This was made evident in a series of communications between the two in 1947, three of which are highlighted below:

In a letter dated April 30, 1947 to the Executive Council of the PNP from WG McFarlane it was noted that, ‘At a meeting of the directors of the Jamaica Progressive League, it was decided to discontinue the affiliation of the league to the PNP [on the basis that it was]

* Not satisfied that by practical demonstrations the PNP has so far lived up to its expectation with respect to the nationalist programme for Jamaica.

* Not satisfied with nor does it approve of the party’s manner or method of criticism of the Bustamante party and Government and views with concern the apparent inability or unwillingness of your party to continue the building up of public opinion by the fullest exposition of such national matters or the transport and cement franchise, excess profits tax, or domestic water supply and electrical frequency which is now publicly discussed and shortly to go before Government for decision.

* The league is unable to view with equanimity, the presence of, on the Executive, and the domination of that committee and the General Council of your party, by a faction whom, declaring itself to be communistic, has created confusion and apprehension in the minds of a large section of our people; and especially, that the president of the party, in a recent communication to an officer of the league, has affirmed his support of that element of the party.

* The league as an affiliated organisation is never invited to discussions even on matters which we are known to be an intrinsic and important part of its programme; also that as at the last annual conference of your party (1946) held at the Ward Theatre, the president deliberately prevented the representative of the league carrying out his instructions with regards to the discussions and criticism of the party’s annual report and statement of policy for 1947.

In these circumstances, the league finds its further support impossible and has further decided to re-establish itself as an unattached and independent political organisation in the cause of Jamaica’s progress.

In the response to this caustic letter from the league, the general secretary of the PNP, on July 19, 1947 noted:

‘The People’s National Party is a responsible body with a duty to the people of Jamaica in their political struggle, concerned only to work in the best interest of the country and under a positive obligation to secure for this country a sane economic and social programme of reform for the benefit of the population as a whole…I am to remind you that the party is democratic in constitution and there is ample opportunity for discussion within the structure of the party of all policies which are pursued, and further that annual conferences, consisting of delegates from all groups and affiliated organisations, have regularly laid down the basic policies. I am to express that your league, perhaps through inactivity, has not availed itself of the opportunity to express its views and endeavour to influence party policies through the means open to them and everybody within the party.

‘I am to categorise as a complete falsehood your statement that the Executive Committee or the General Council of the party is dominated by a faction declaring itself to be communistic, or by any faction of any nature whatsoever, and your statement that the president of the party had affirmed his support of such an element in the party in any communication addressed to your league or to any officer thereof.

‘In connection with a statement contained in your letter that a representative of the league was deliberately prevented from participation in debate in the annual conference…that your league would have no ground for the complaint if it had been careful to select a representative willing to assist in the orderly carriage of business instead of a person who consistently endeavoured to flout the standing orders of the assembly and to abuse the dignity of the chair.

‘Express…regret that your league should have been induced to discontinue their affiliation…’

This strongly worded letter from the PNP did not go down well with the Jamaica Progressive League which fired off another tart response on 25 July 1947:

‘Your letter is so full of misstatements, inaccuracies and misrepresentations which have become the greatest proof of the wisdom of our belated decision to sever our connection with your party. Our greatest regret is that those of us who influenced the decision of our league to become entangled in your web in 1938 have now come to bow our heads in shame to a minority who were opposed to the affiliation that this group was right.’

The league remained resolute in their advocacy for self-government, although their role was gradually lost in the magnanimity of the PNP and its charismatic leader, Norman Manley. They became so frustrated with the efforts that McFarlane eventually closed the Jamaica Progressive League in Jamaica and submitted the files to the Institute of Jamaica. Another local chapter was eventually opened in 1986 by Frank Gordon, Jimmy Tucker, Roy Johnson, and others who felt the need keep the league alive.

Despite Manley’s failure to remain committed to the mandate of the league and the breakdown in the relationship, he remained mindful of the part they played. In his eulogy to Edward Jordon, late member of the league, Manley said:

‘The Progressive League, as you know, is the first organisation to raise a strong voice for self-government for Jamaica. It is the first organisation to demand that we try to develop a national spirit in this country.’

Also, upon the country’s attainment of Independence in 1962, he invited Domingo, with whom there had been a difference of opinion on the issue of federation. Despite Domingo’s membership in the party, he remained committed the ideals of the Jamaica Progressive League and thus, like the league, could not support anything that was less than immediate Independence. Domingo later thanked him in a letter dated 1963, noting that when he attended the Independence celebration in August 1962, he was not aware that it was upon Manley’s invitation and was surprised to learn that, considering their strained relationship because of his opposition to federation.

Conclusion

The Jamaica Progressive League did not manage to attain the revolutionary attitude towards the political structure during the period when they were most visible. However, attitudes were slowly changing. The efforts of the league and the growth of pan-Africanism helped to mould the minds of Jamaicans at home and in the Diaspora as well. So too did the increased migration to Britain in the 1950s.

The United States placed restrictions on travel to that country, and so many turned instead to Britain in what was the largest wave of emigration in the country’s history (1950s and 1960s). The increased travel to Britain played an important part in changing perceptions about Jamaica’s connection to the British Empire. As Nancy Foner explained in her study of Jamaican migrants in London, interactions with British people on their home turf forced many Jamaicans to dispel previously held feelings of attachment to Britain. She quoted a Mr Charles who noted:

“We didn’t feel strangers to England. We had been taught all about British history, The Queen and that we ‘belonged’. When I got here it was a shock. A shock to discover people knew nothing about us. I discovered we weren’t part of things. My loyalty at age 15 was to England. I felt that Jamaica was part of England. The shock was to find I was a stranger.”

The sense of otherness which the migrants in America experienced was now shared by so many other migrant Jamaicans. The soap boxes that characterised the street corners in Harlem were also evident in Britain, such as was the case at Speaker’s Corner in Hyde Park where migrants sought to not only express their disgust with the treatment meted out to them, but to also call for “the right to govern the country where we were born”.

This psychological detachment from Britain in the mid-20th century helped to give life to the concept of nationalism which was based on the attachment to the land of their birth, a desire to obtain full possession of their land, and the predominant commonality of blackness. This had been fomenting from the 1930s and, as the sentiment grew, middle class society began identifying with it in an effort to further their national programme.

The nationalist sentiment seemed to have been close to its peak during preparations for the Independence celebrations. The Independence Committee was flooded with requests from across the island, as well as from the Diaspora in Britain, Panama, and New York, so much so that the chairman of the committee, Theodore Sealy, suggested that a mission be set up to deal with these.

Many had their own ideas of how the occasion should be marked. Mike Williams-Thompson, international public relations consultant in London, suggested the establishment of a ‘Jamaica Day’, special newspaper articles on ways in which Jamaicans settling in Britain are integrating, a travel exhibition on Jamaica, an essay competition, and a cocktail party for Princess Margaret.

In the quest to nurture this burgeoning concept of nationalism, the Independence Committee selected a motto — Out of Many, One People — which, it was hoped, would serve to further entrench this sentiment.