Political awakening (Part 3)

The idea of black self-determination led to the beginning of a movement which Alain Locke, a black American intellectual, described as a ‘spiritual coming of age’ of the black community. It was called the ‘New Negro’ Movement after Locke’s 1925 anthology. The ‘Old Negro’ was viewed either as one who looked to the white man to institute change, pandering to his whims and fancies, vainly hoping that a hand of mercy would one day be extended or even worse, he was one who unreservedly accepted the lower rank the white man assigned him in society. His inability to break away from the psychological stranglehold of the past caused JA Rogers to offer the following descriptions of him:

“One can hear the clank of the slaver’s chain in all that he says and does.”

And

“Shut your eyes when he speaks and you’ll hear a cracker talking.”

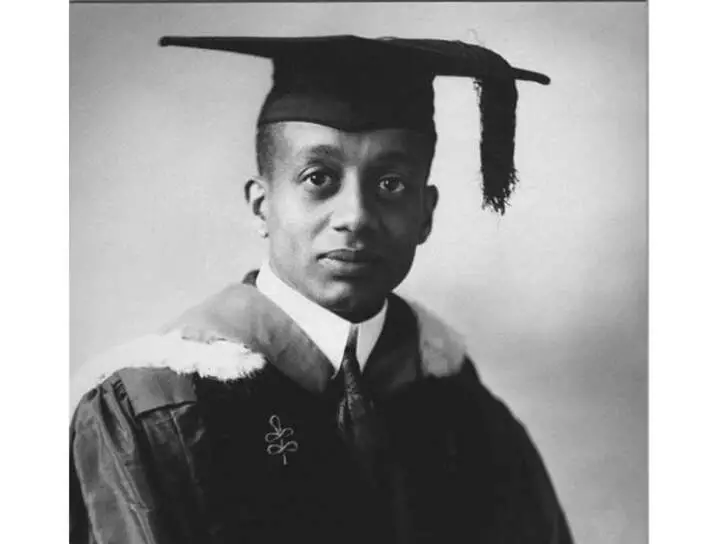

The reward for the Old Negro attitude was only disappointment and the New Negro was cognisant of this. Who exactly was this New Negro? Jamaica’s Walter A Domingo, who later helped to form the Jamaica Progressive League, offered his understanding of the New Negro in a 1920 publication of the Messenger. According to Domingo, the New Negro was one who “cannot be lulled into a false sense of security with political spoils and patronage. The job is not the price of his vote … “

The New Negro, therefore, could not be bribed. He was aware of the unwillingness of whites to facilitate any genuine advancement of the black race. His rejection of the notion that he was inferior and his steadfast determination to attain equal status made the New Negro realise that it was incumbent upon him and his people to bring about change. It was clear that change could only come from within the black community.

They had to demand and secure change if it were to ever be a reality. Essentially therefore, the New Negro reflected a rejection of the past status quo of black people and a determination to assert the rights of people of African descent to civic participation, political equality, economic freedom, and cultural self-determination.

The New Negro Movement was later called the Harlem Renaissance out of recognition of this locale as a major hotbed of the movement. However, it was not restricted to any one location as it was, after all, not an expression of black Americans in Harlem, but was, in fact, an articulation of a confluence of black people drawn from different regions in the United States and the West Indies who shared experiences of political and economic discrimination. Thus, the term ‘Black Renaissance’, which is also one of the names ascribed to the movement, is quite befitting.

Not only were Jamaican migrants conscious of the existence of the New Negro Movement, but they played prominent roles in it as well. Claude McKay, for instance, was credited as the writer who ignited the Harlem Renaissance with his publication of Harlem Dancer in 1918. The works of West Indians, literary or otherwise, helped in defining the character of the New Negro.

Marcus Garvey was one of the most influential intellectuals of the movement who galvanised international support for the principal ideals of race-consciousness and black enterprise. There were also those who later formed the Jamaica Progressive League. Other eminent West Indians who contributed to the growth of the Black Renaissance included street orators such as Hubert H Harrison from the Virgin Islands, Richard Benjamin Moore from Barbados, and Frank R Crosswaith from St Croix. There were also writers such as Cyril Valentine Briggs from Nevis, Arturo Alfonso Schomburg from Puerto Rico, and Eric Walrond who had roots in both Guyana and Barbados. Photographer Austin Hansen (Virgin Islands) and labour organisers and political activists Hubert Harrison, Ashley Totten, and Elizabeth Hendrickson (all of St Croix) were also included in this group.

These radical migrant intellectuals emerged during a period in American history when it can be said that there was a vacuum in black leadership. Their migrant status made them integral to that process of change, perhaps because as travellers they got a better understanding of the plight of the black man, having sojourned far from the land of their birth and witnessed and/or experienced the victimisation of blacks everywhere they went.

Through their travels, they were able to confirm that there was no safe haven for the black man. Racism and inequality in the distribution of resources were not confined to their homeland. It was evident everywhere as Garvey found.

“I was determined that the black man would not continue to be kicked about by all other races and nations of the world, as I saw it in the West Indies, South and Central America and Europe, and…I read of it in America,” he said.

Not only did they comprehend the magnitude of the black man’s problem, but the active tradition of black involvement in the anti-colonial politics in the colonies from which they came prepared them to lead the effort.

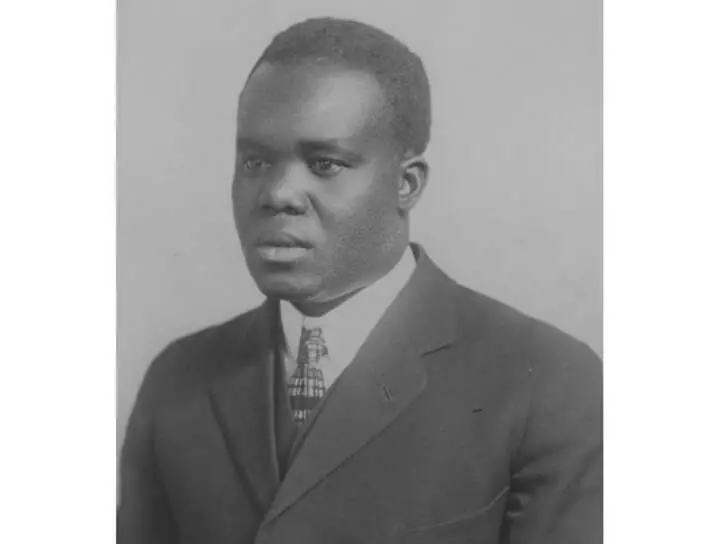

Post-emancipation Jamaica, for example, had the likes of Dr Joseph Robert Love who lobbied for black representation in the colonial legislature and himself was elected to the Kingston City Council in 1898 and, eight years later, to the Legislative Council. In fact, Garvey confirmed the impact of such a stalwart when he credited Dr Love for his race consciousness.

Participation in anti-colonial organisations, such as the National Club, also helped to groom those migrants who emerged as leaders of the movement. Both Garvey and Domingo, for example, belonged to this club. Rupert Lewis noted that “the National Club was formed by SAG Cox, a near-white city barrister who had been discriminated against in the civil service and who was said to have been influenced by the Sinn Fein movement”. The Club called for “self-government within the Empire, similar to that of Canada and Australia”.

Migrant Jamaican intellectuals applied their experiences of fighting against imperialism in Jamaica to the problem of white domination in the United States. Later, Jamaica would benefit from the knowledge gained in the United States.

TOMORROW: In search of a homeland

— Kesia Weise is a researcher at the African Caribbean Institute of Jamaica/Jamaica Memory Bank