Catch A Fire at 50

When it was released in April 1973, Catch A Fire by The Wailers was a sensation. Its songs were as bold as its unique album jacket and reflected the uncompromising pose of Bob Marley, Peter Tosh and Bunny Livingston.

Next month marks the 50th anniversary of the album’s release by Island Records. It capped the global emergence of reggae and came one year after The Harder They Come was unleashed to similar rave reviews.

Marley and Island Records boss Chris Blackwell are credited as co-producers of the nine-song album, The Wailers’ first for a recognised label. Initially recorded with Jamaican musicians in Kingston at Harry J, Randy’s and Dynamic Sounds, Blackwell enlisted American and British session musicians for finishing touches at Island’s studio in London, to achieve an international flavour.

American guitarist Wayne Perkins’ searing solo on Concrete Jungle did the trick and Catch A Fire caught on among free-spirited music fans like Roger Steffens, who was living in Southern California.

“In late June 1973, after reading The Wild Side of Paradise in Rolling Stone (magazine) by Australian Gonzo journalist Michael Thomas, which introduced reggae to America, I ran out from my apartment in Berkeley searching for a copy of Catch A Fire. I found a used disc in Pellucidar Books on Shattuck Avenue for $2.25 and figured I could take a chance,” Steffens recalled. “When I dropped the needle on Concrete Jungle I jumped back a bit, unused to the unusual ‘riddim’ and scintillating guitar. Then the poetry kicked in. I’d been reading poetry in schools for a living since 1966, and it was the lyrics as much as the music that drew me in so deeply right from the start.”

In Jamaica, not many people knew what to make of the album. Winston Barnes, a 22 year-old disc jockey at the Jamaica Broadcasting Corporation (JBC), was not overly impressed.

“To be honest, I don’t remember it being out of the ordinary where the music is concerned, I was already immersed in Marley’s music from the mid-60s when I met him. In addition, JBC was always open and receptive to things Jamaican more than RJR (Radio Jamaica),” said Barnes. “I’m hoping it is not just hindsight but for me the music was moving away from being just parochial, just Jamaican but moving to what Rastaman call the ‘univerShal’.”

The gifted Marley wrote seven of the nine songs on Catch A Fire, including Concrete Jungle which featured a 21-year-old bass player named Robbie Shakespeare. He also wrote Slave Driver and Stir it Up, while Tosh composed 400 Years and Stop That Train.

Marley, Tosh and Livingston were original members of The Wailing Wailers which formed in Trench Town in 1963. They scored a number of ska and rocksteady hits before embracing reggae in the late 1960s with producer Lee “Scratch” Perry.

The eccentric Perry produced edgy songs like Soul Rebel, Small Axe and Mister Brown, played by The Upsetters, his house band which included the Barrett brothers (Aston and Carlton) on bass and drums, respectively.

The Barretts had pivotal roles on Catch A Fire. Marley played rhythm guitar and handled most lead vocals; Tosh played guitar, organ and piano while Livingston played percussion.

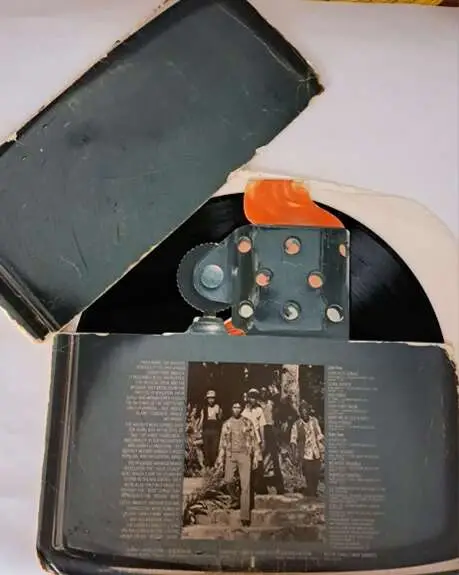

Catch A Fire earned strong reviews in major publications like Rolling Stone and Village Voice. The former called it a “blazing debut”. Its original jacket, in the form of a Zippo cigarette lighter, also stood out.

Sales, however, were not as enthusiastic. Catch A Fire peaked at number 171 on Billboard Magazine’s 200 Chart and reached number 51 on the publication’s R&B table.

In six months, Island Records released Burnin’, its second Wailers album. By 1974, Tosh and Livingston left the group, citing differences with Marley and the label about its direction.

Marley, who died from cancer in 1981 at age 36, became a superstar through a series of outstanding albums distributed by Island. Tosh also had a storied career that ended when he was murdered at his St Andrew home in September 1987 at age 42.

Livingston, who became Bunny Wailer, cut several strong albums including Blackheart Man and Rock ‘n’ Groove, and won three Grammy Awards for Best Reggae Album. He died in March 2021 at age 73 after suffering several strokes.